Music as torture

Music is, perhaps, the only art form used as a means of torture. Amongst CIA interrogation techniques employed for coercive purposes is a list of songs and performers reportedly used to “torture” detainees that British human rights group Reprieve has posted on its Web site. This sinister catalogue of tunes ranges from AC/DC’s Hell’s Bells, a heavy-metal ditty that sounds as though it had been recorded by an orchestra of chainsaws, to such seemingly innocent fare as Don McLean’s American Pie and the Bee Gees’ Stayin’ Alive. Most of the records cited by Reprieve have one thing in common: they are deafeningly loud. But the presence on the list of songs from the children’s television programs Barney the Dinosaur and Sesame Street, staples of USAmerican children’s TV programming, suggests that the successful use of music as a tool of coercion entails more than mere volume (for more on this see Wikipedia 2003–2022, and Teachout 2009).

The shrieks and groans of recorders in the hands of children and enthusiastic amateurs sometimes seem to offer a foretaste of eternal torment. There is nothing new about this association. Indeed, since its very first appearance, the recorder has been associated with torture.

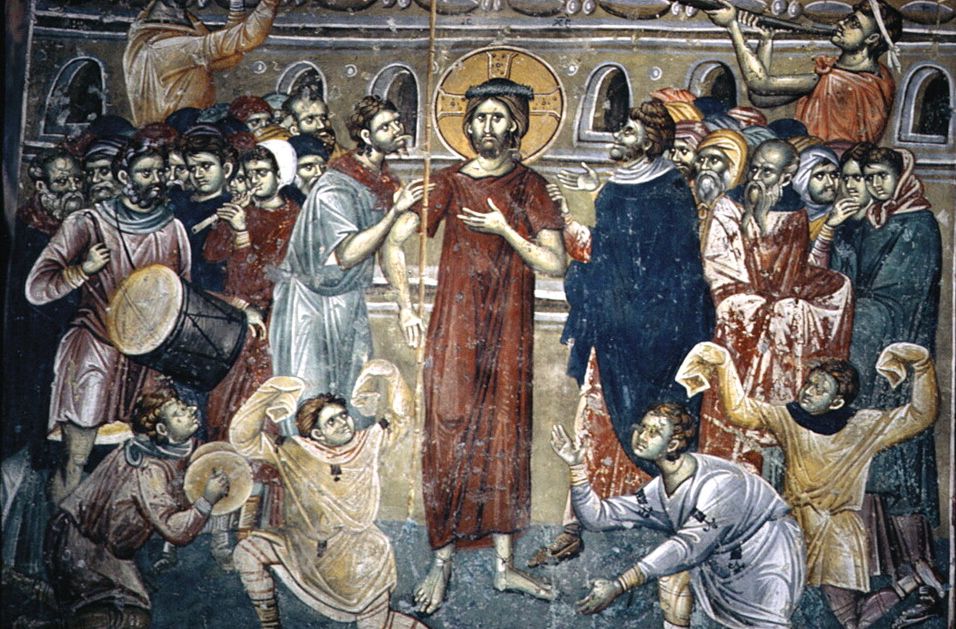

The Mocking and Crucifixion of Jesus

From my survey of more than 4,000 depictions of the recorder (Lander 1996—2026), the very earliest illustration of a recorder as such is in The Mocking of Jesus (after 1315), a fresco from the Church of St George, Staro Nagoričane, a village near Kumanova in (Yugoslav) Macedonia, by the court painters Michael Astrapas and Eutychios, in which a musician plays a cylindrical recorder, the beak and window/labium of which are clearly visible, as are open holes beneath three lifted fingers of the player’s uppermost (left) hand and four holes for the fingers of the lowermost hand which are also off the instrument.

This painting is very different from the stereotyped frescoes of the same period found elsewhere in the region, and it may record a theatrical performance of an earlier time. Data from the religious literature of thirteenth-century Serbia reveal that church authorities forbade their congregation to attend gatherings where actors performed. In the work Eulogy to Saint Simeon and Saint Sava, Teodosije (1264–1328), a monk at the Serbian monastery of Hilandar and a writer, pointed out that opposed to the heavenly beauty of the church was “the actor’s odious theatre” which had been organised on the street and to which people gathered, regardless of the weather, where they watched and listened intently to harmful devilish songs replete with indecent, rude words. The traits of once-staged scenes and old sports festivities lived on in the Serbian milieu during the fourteenth century as well (Marjanović 1995).

Although not mentioned in biblical accounts, a number of depictions of the mocking of Jesus include musical instruments as implements of his torture. Of these, only two others include a recorder: both show the various humiliations Christ suffered before his Crucifixion; and both appear to draw on Albrecht Dürer’s The Mocking of Christ woodcut of circa 1508-11 that was included in his influential Small Passion print series (Koepplin 2018). However, the depiction of this scene by Astrapas and Eutychios (see above) hints at a much older tradition.

Cranach’s painting conflates the various Gospel accounts given of the mocking of Christ and shows him already clothed in a robe of royal purple, in which he was dressed before he was crowned with thorns. Each of the figures mocking Christ is given exaggerated, grotesque features, emphasising their sin in mocking Christ and heightening the humanity of Christ’s suffering. Described in Psalm 22 as “dogs . . . the assembly of the wicked”, each is engaged in a different form of mockery, from the man in the red hat who pokes his tongue out at Christ, while pulling a lock of his hair, to the two men who prepare some fouled water which another sprays into Christ’s face, and the Roman soldier who mocks the partially blindfolded Christ by putting a duct flute (probably a recorder) to his lips. A copy of this work is in the Castle Picture Gallery, Prague; another was auctioned by Lempertz, Cologne, in 2013.

In Maththias Grünewald’s Mockery of Christ (1503), in the Alte Pinakotheck, Munich, one of the Christ’s tormentors (at top left) plays a clearly depicted tabor pipe. An anonymous copy of this painting in the Muzeul National Brukenthal, Sibiu, is close to the original but the copyist has substituted an equally clearly depicted soprano/alto-sized duct flute with seven in-line finger holes and a flared bell for Grünewald’s shorter, cylindrical pipe. The instrument is a little slender for a renaissance recorder at its upper part, but otherwise it certainly seems to be a recorder. The fingers, all well-painted, are held in a manner which looks as if they are playing the instrument but in fact bear no relation to the positions of the finger holes.

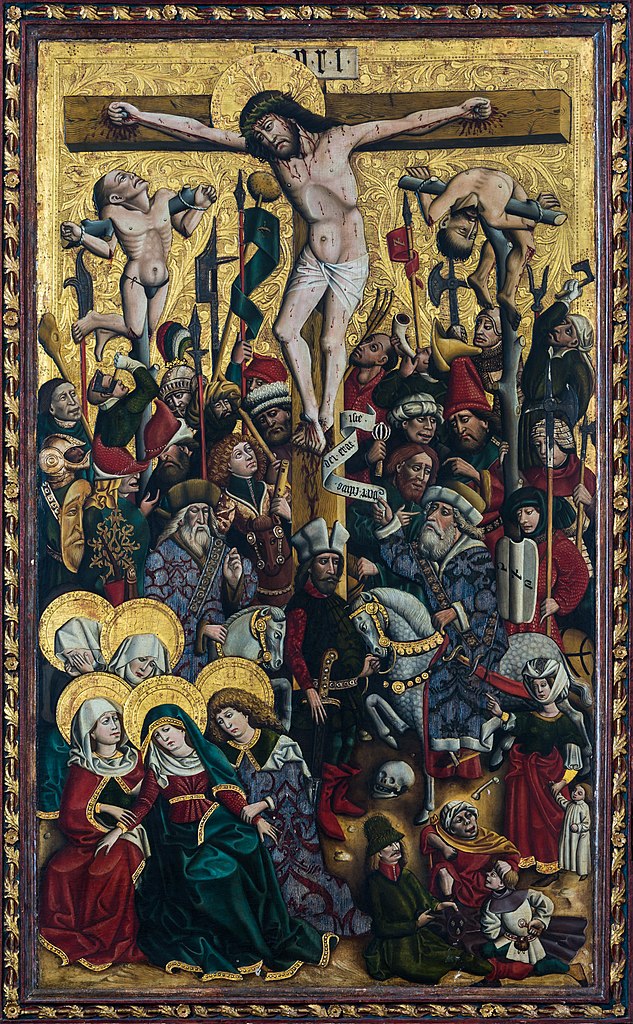

A continuation of the mockery of Christ can be found in an anonymous Crucifixion (c.1450) in the Pfarrkirche Mariä Himmelfahrt (Maria am Berg), Halstatt. The striking central panel of the Knappenaltar (altar of the miners) depicts Christ on the cross between the Good Thief and the Bad Thief who are tied in excruciating positions. Beneath them are stern-faced clerics on horseback, and a rabble of spectators clamouring and waving weapons. Three musicians amongst the crowd blow a horn, shake a rattle and hold a stout, cylindrical recorder, the beak, windway, window/labium of which are are clearly visible. In the foreground left are the Three Marys. To the right a woman holds a child’s hand and points up to Jesus. In the lower right-hand corner two men and a youth are gambling.

Allegory of Vice

The recorder appears again as an instrument of torture in Antonio Allegri Coreggio’s Allegory of Vice (c. 1530). Here, three female figures torment a bearded man who is tied to a tree. In the foreground is a grinning boy. The man was identified as the satyr Marsyas by the writer of the Gonzaga collection inventory of 1542. Subsequently he has been identified variously as a personification of Vice, or as Silenus, or Vulcan. Perhaps he represents a conflation of all these figures from classical antiquity.

Taking the simplest path, it can clearly be seen that the three women are the Furies (Erinyes/Dirae), easily recognised by the livid snakes in their hair. Their number is usually left indeterminate, but the three sisters Alecto, Tisiphone, and Malea are often named. Their task is to hear complaints brought by mortals against each other, and to punish their vices and crimes by hounding culprits relentlessly and tormenting them to madness. Here, their victim is a shepherd whose unattended flock can be seen grazing in the distance. Alecto torments him with hands full of snakes (perhaps for the slothful neglect of his flock). Malea (recognizable from her blood-stained cloak and the serpent around her waist), has started to skin him alive, starting at his left ankle (perhaps indicating his hubris by analogy with Marsyas, who was flayed alive by Apollo). And Tisiphone blows a cylindrical duct flute (probably a recorder) in his ear (perhaps indicating his lechery as well as further reminding us of Marsyas). The grinning boy in the foreground is holding a bunch of grapes and reminds us of Bacchus and his follower Silenus, echoing both the shepherd’s sensual nature and his consequent ritual insanity at the hands of the Furies.

An engraving of this painting by Etienne Picart (1632–1721) — London: British Museum: Inv. 1837,0408.285; Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria, Inv. p.183.7-1; Princeton University Library, Graphic Arts Collection, Inv. GC077 — bears a caption describing the sensual man as enchanted by lust, bound by bad habit, and tormented by conscience.

Children Tormenting a Cat

In Steen’s Children Teasing a Cat an old man smoking a pipe watches three children torment a cat. A girl holds the animal up by its front paws as it kicks its rear legs in the air, as if dancing; a boy is about to dip its tail in a tankard of beer; another boy squawks away on a small duct-flute, possibly a recorder. And the old man appears to be blowing pipe smoke in the poor cat’s face.

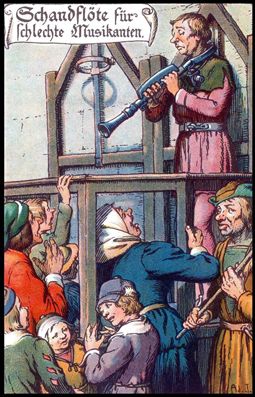

The Flute of Shame

Contrariwise, devices resembling recorders but designed as instruments for actual physical rather than auditory punishment can be found in museums and in artworks from northern Europe, the so-called Schandflöte or “flute of shame”.

Surviving instruments of torture in the form of the recorder, trumpet trombone, oboe, etc., made of brass or iron are probably of Dutch origin and, for the most part, date from the 17th and 18th centuries, although examples from earlier and later sources are also known. The iron necklace was closed behind the neck of the victim whose fingers were positioned like those of a musician under the notches in a clamp which was tightened by means of the screws, enabling the application of pain or the crushing of flesh, bone, and gristle.

Such torture was essentially a form of public humiliation with all the attendant painful and sometimes fatal consequences that accompany a fall from grace. It was used to punish misdemeanors: disbelief, blasphemy, speaking against the order, etc.

Some modern commentators have suggested that these instruments were for the castigation of incompetent musicians but, in an age when torture was commonplace, bad musicians were more likely simply removed from the band or orchestra, whereas their occasional indiscretions, like those of any other craftsmen, were met with a cuff about the ears rather than torture or mutilation.

References

- Castellano, Manuel. 1996. La flauta del aboratador [The torturer’s flute.] Revista de Flauta de Pico 6: 39.

- Koepplin, Peter. 2018. “From a French Private Collection: Lucas Cranach I (Kronach 1472-1553 Weimar)”: The Mocking of Christ. Christies Live Auction 14772 Old Masters Evening Sale Lot 13. 2018.

- Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2023. Recorder Home Page: Recorder Iconography.

- Lasocki, David R.G. & Ehrlich, Robert. 2023. The Recorder. Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

- Legêne, Eva. 2005. “Music in the Studiolo and Kunstkammer of the Renaissance, with Passing Glances at Flutes and Recorders.” In Musique de Joye: Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Renaissance Flute and Recorder Consort. Utrecht 2003, 323–61. Utrecht: STIMU Stichting Muziekhistorische Uitvoeringspraktijk (Foundation for Historical Performance Practice).

- Marjanović, Petar. 1995. The Theatre. In The History of Serbian Culture, edited by Pavle Ivić, transl. Randall A. Major. Edgeware, Middlesex: Porthill.

- Mittelalterliches Kriminalmuseum, Rothenburg ob der Tauber, ed. (1989). Justiz in alter Zeit [Justice in old times.] Schriftenreihe des Mittelalterlichen Kriminalmuseums Rothenburg ob der Taube, Band VLC, S 469.

- Stivini, Ordoardo. 1542. Inventario delle gioie di Isabella d’EsteInventario delle gioie di Isabella d’Este [Inventory of the possessions of Isabella d’Este Gonzaga]. Mantua, Archivio di Stato di Mantova, Inv. b. 400.

- Teachout, Terry. 2009. Musical Torture Instruments: Can being forced to listen really be that painful? Wall Street Journal 14 February 2009.

- Wikipedia 2003–2022. Music in psychological operations.

Cite this article as: Nicholas S. Lander. 1996–2026. Recorder Home Page: The Recorder as an Instrument of Torture. Last accessed 10 March 2026. https://recorderhomepage.net/the-recorder-as-an-instrument-of-torture/