It was long thought that the only surviving, more or less complete, medieval musical instrument conforming to the definition of a recorder given above was the Dordrecht recorder, held in the musical instrument collection of the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (#544045) until 2009 when it was removed to the Dordrecht Museum (inventory number 4001.000.008). It is currently on permanent display at Het Hof van Nederland, Dordrecht.

The Dordrecht recorder was discovered in 1940 and was first described by Thijsse (1949) with a photograph and short description in a work on the history of music in that area of the Netherlands. Subsequent accounts were provided by Gleich (in Weber 1976), van Acht (reported by Rowland-Jones 1996), Hijmans (2015), Hijmans et al. (2016), and Popławska & Lachowicz (2014). Briefly, the Dordrecht recorder was excavated from a well (not a moat) at the Huis te Merwede (House on the Merwede) about 3 km east of the town of Dordrecht, Holland. This castle was founded in the first quarter of the fourteenth century and was the residence of a wealthy Dutch family from 1335. An assault in 1418 and the devastating effects of the St Elizabeth Flood of 1421 and another in 1423 put an end to the existence of the castle. Not until the nineteenth century was the area lying around the castle drained. The excavations in 1940 revealed some 30 objects, including a recorder.

Thus, two circumstances in connection with the Dordrecht recorder are extremely fortunate. Firstly, on account of the short period during which the castle was inhabited (1335–1418) the dating of the instrument’s deposition seems to fall within clear limits. Secondly, the recorder has remained submerged, untouched until its excavation. Furthermore, the well in which it was found was built during the second phase of construction of the house, shortly before the mid-14th century. Bouterse (1995) notes that this instrument is possibly a few centuries older than that suggested above. However, Hakelberg (1995: 11) argues that it is rather unlikely that the Dordrecht instrument dates from the thirteenth century, since the written sources show that the donjon was built in the first quarter of the fourteenth century, and there is no archaeological evidence of an earlier medieval settlement on the site.

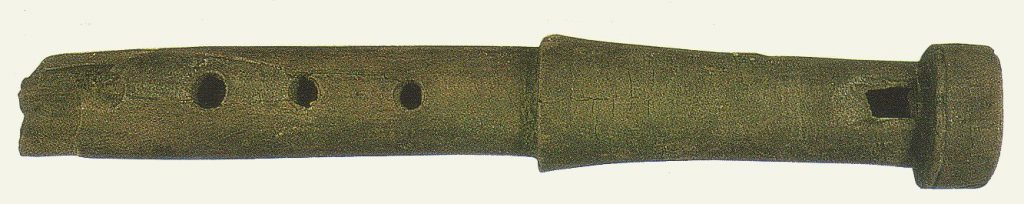

A comprehensive description of the Dordrecht recorder was provided by Weber (1976). Further details are given by Fitzpatrick (1975), Carlick (1975), Reiners (1997), Hijmans (2015) and Hijmans et al. (2016). The instrument is in good condition and is not imperiled. Its external outline is cylindrical. It is made of close-grained fruit-wood, possibly plum-wood. Its vibrating air column is cylindrical, 275 mm long (measured over the external curve of the instrument), and the internal bore is 12.3 mm at the most. The block is cylindrical and projects 3.5 mm into the mouth of the instrument. The cut-up of the mouth is 7.5 mm high and its ears are splayed outwards. The windway floor is quite flat. The seven finger holes are widely spaced, a function of the narrow, cylindrical bore. The lowest finger hole is doubled to allow playing by right- or left-handed players, the hole not in use being plugged. Both ends of the instrument are turned to form tenons, the one at the upper end with two external, circumferential grooves. The mouthpiece is truncated rather than beak-shaped. The lower tenon is slightly tapered. Due to damage to the labium of the recorder, it cannot be sounded.

A more or less complete medieval recorder dating from the fourteenth century, the Göttingen Recorder, has been reported from northern Germany where it was found in a latrine in Weender Strasser 26, Göttingen, in 1987, together with numerous other items, such as glass and dice.

Now part of the collection at the Sammlung des Musikwissenschaftlichen Seminars der Universität Göttingen, it has been described by Hakelberg (1995), Hakelberg and Arndt (1994) Homo-Lechner (1996), Reiners (1997) and Doht (2006). More recently, it has been CT scanned by the Institut für Medizinische Physik der Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (Kalender et al., 2009). The instrument is in one piece and has vents for seven fingers and a thumb hole. The seventh hole, for the little finger of the lower hand, is doubled. The instrument is 256 mm long and is also made of fruitwood (a species of Prunus). Its beak is severely damaged, which probably explains why it was discarded. It’s bore has a diameter of 13.6 mm at the highest measurable point. There are narrowings of the bore to 13.2 mm between the first and second finger holes, to 12.7–12.8 mm between the second and third finger holes, and a marked contraction to 11.5 mm behind the seventh (doubled) hole. The bore expands to 14.5 mm at the bottom of the instrument which has a distinctive bulbous foot, possibly indicating double duty as a drumstick. Curiously, the finger holes are widened toward the exterior rather than undercut; this is clearly visible in the CT scans (Kalender et al., 2009).

Hakelberg (2002 & pers. comm. 2003) reports that a fourteenth-century recorder fragment, the Esslingen Recorder, has come to light. It was found near Stuttgart, Southern Germany, where it was excavated from the sediment of the mill channel of the Karmeliter-Monastery, Esslingen which existed from 1271-1557.

Hakelberg is of the opinion that the broken light coloured fragment is of boxwood, the better preserved of fruitwood (length c. 25.5 cm), with holes for the thumb and five fingers. Unfortunately, during conservation ca 10 cm of the instrument has been lost. Interestingly, it shows the very same characteristic turning profile as the Göttingen recorder. These fragments are preserved in the Landesdenkmalamt Baden-Württemberg, Stuttgart.

A fourteenth-century recorder, the Tartu Recorder has been found during an archaeological dig in August 2005 by Andres Tvauri in Tartu, Estonia near the border with Russia (Tvauri and Bernotas 2005, Tvauri & Utt 2007, Utt 2006), now preserved in the Tartu Linnamuseum

Like both the Göttingen and Esslingen instruments, the Tartu recorder was also found in a latrine, in the backyard of 15 Üikooli Street. Other artifacts found with the Tartu recorder allow it to be dated from the second half of the fourteenth century. During the late medieval period Tartu was an important Hanseatic city connecting Russia, especially Novgorod, with Western Europe. The house where the recorder was found seems to have been that of a wealthy person. The head of the instrument is turned with ornamental rings. The only crack is at the foot of the instrument and does not extend into to the bore. The body of the Tartu recorder is made from maple; the block from birch. Like the Elbląg and Copenhagen recorders (see below), there is a flattened surface on the front of the instrument extending almost its full length. The total length is 24.7 cm and the sounding length 22.5 cm. Thus, the instrument is of similar size to a modern sopranino at 440 Hz. Utt notes that in its current state it has a compass of ninth, but that due to shrinkage and damage to the voicing this may represent a reduced range. A hole was drilled through the head of the instrument and through the tenon, perhaps to thread a thong with which to hang the instrument. Amongst the other artifacts found with the recorder was a fourteenth-century stoneware jug which originated in Southern Lower Saxony, presumably imported in the Hanseatic trade. It is reasonable to conjecture that the instrument might also be of North German origin.

A fragment of another possible medieval recorder, is preserved in the Mainfrankisches Museum at Würzburg in Germany (#50779) which has been dated between 1200 and 1300 (Moeck 1967). The WürzburgFragment was found during an archaeological excavation of the Salhof (manor house) of Würzburg where it was located in a well and also dates from the fourteenth century. However, only the bottom part of the instrument has survived. Kunkel (1953) and Weber (1976) have described this fragment in considerable detail. It is made of fruitwood (again, a species of Prunus). In its bore and the size and disposition of its finger holes it corresponds closely to the Dordrecht recorder. A curious feature of the Würzburg fragment is the presence of a small lateral hole just above the end of the bore. A shallow external groove is inscribed around the circumference of the fragment near the end of the bore. A crack runs through the lateral hole. Hakelberg (1995: 11) argues that this fragment cannot be identified with complete certainty as part of a recorder and that it could well be part of a reed-pipe instrument.

Another possible medieval recorder has been reported by Jack Campin of Edinburgh (pers. comm., 2005). The Rhodes Fragment is a bone flute is housed in the Museum of the Palace of the Knights of St John at Rhodes, tucked away inaccessibly in a rarely-opened glass case. The head is missing, but it is probably a duct flute, as reed instruments were more likely to be made of cane. Campin writes that it has “holes in the usual recorderish places, including the thumb hole; it looks very much like my Susato G sopranino”. The Knights were at Rhodes from 1309 to 1522, before they withdrew to Malta in the face of the advancing Ottomans. This bone-flute has not yet been more closely dated, and it is possible that it could have been made before 1400 (Rowland-Jones 2006: 14). In the late fourteenth century, and well into the fifteenth century, there were cultivated Aragonese courts with musical establishments in Cyprus and Sicily that the Knights would almost certainly have visited. But as Campin remarks, this fragment could have originated anywhere from Portugal to the Ukraine.

A medieval recorder was been found in 1998 in a latrine in the old Hanseatic city Elbląg (in former times Elbing) southeast from Danzig in Poland, and is housed in the Muzeum w Elblągu (Naumann 1999, Kirnbauer and Young 2001, Kirnbauer 2002, Poplawska 2014). The Elbląg Recorder is intact and has been dated to the mid-fifteenth century. It is made of maple in one-piece 30 cm long and appears to have a vibrating air column of 27 cm. Like the Dordrecht, Göttingen and Tartu recorders, the Elbląg recorder lacks the beak-shaped mouth-piece characteristic of the modern instrument. And like the Tartu (see above) and Copenhagen (see below) recorders, the front of the instrument has a flattened surface on the front of the instrument extending almost its full length. Carefully worked details of this recorder, including undercut finger holes and the edge of the labium point to a professional maker. This is supported by the presence of a maker’s mark in the form of a circle with a central dot burned in the top of the instrument. Again, the lowest interval of the Elbląg recorder seems to have been a semitone. It was thus likely to have been pitched around d’, a tone higher than a modern soprano recorder.

Mateusz Lacki (pers. comm. 2011) reports that a fourteenth-century recorder found after the Second World War in a latrine in the city of Nysa in Silesia, Poland, dating from 1350-1420, is housed in the Muzeum Powiatowe w Nysie (Tonderę1966; Popławska & Lachowicz 2014); Lasocki 2023). The Nysa Recorder, made from elderwood (Sambucus nigra), is ca 31.7 cm long. Although the block is missing, details of the window and labium are unmistakable. The blowing end of the instrument is truncate rather than beaked. The bore is slightly obconic, ranging from 16 cm at the top to 14 mm at the foot. It has single holes for seven fingers as well as the usual thumb hole. Again, the lowest interval of the Nysa recorder seems to have been a semitone.

In 2011, a recorder made from a single piece of narrow-grained spruce wood was discovered in Puck, Poland, where it was excavated from a latrine built in the 14th century on a plot adjacent to the town market, currently at 1 Maja Street. Various everyday objects were dug up together with the Puck Recorder. All objects, including the recorder, have been dated to the late 14th to mid-15th century (Blusiewicz 2011).

The Puck recorder has been preserved in its entirety. Its total length is 25.9 cm, with a bore 14 mm wide at the block line, narrowing to 10.1 mm at the foot. The block is fixed in such a way that its annual growth rings were perpendicular to those of the recorder’s wall. The length of the air column is approximately 22.7 cm. There is a thumbhole for the uppermost hand, and seven single finger holes in the top of the instrument, the lowermost one offset to the right. Below the labium opening is a shallowly engraved circle 4 mm in diameter. Again, the lowest interval is a semitone.

In 1997, a recorder was discovered on the plot at today’s 6 Grodzka Street in Płock (Gołembnik 2000). It comes from the late 15th century, which was confirmed by a dendrochronological study. Currently, it is in the Mazovian Museum in Płock (MMP/Dep/991/17).

Like the flute from Nysa, the Płock Recorder was made from a single piece of elder wood (Sambucus sp.). It is in good condition and the instrument has been preserved in its entirety. Its length is 35.5 cm. The bore is cylindrical. The rectangular window is damaged. The underside of the labium is slightly concave and cut at a distance of 32 mm from the block line of the instrument. The length of the air column is c. 32.9 cm. There are seven in-line finger holes. As well as a thumbhole on the underside of the recorder, a second hole is positioned slightly to the side of the recorder’s axis. Its task was probably to correct the intonation, or it was used to thread a thong with which to hang it. The form of the mouth of the instrument is simple, without any decoration. There are several longitudinal cracks in the body, and on the surface, especially at the lip hole, there are small losses of wood. The block of this instrument has not been preserved.

In earlier times moats, mill-channels and wells were probably all pretty putrid and not so different from latrines. Thus, it is tempting to give significance to the observation that seven of the surviving unequivocal medieval recorders described above were found in such foul places, where they may have been discarded. However, the key fact linking these finds is surely not scatological, nor is it that the instrument were all discarded (a mere surmise, although there is convincing evidence that this was the case with the Dordrecht Recorder). It is simply that all these environments involve water which allows wooden articles to survive for long periods.

The transitional instruments described above (those with the lowest interval a semitone) certainly represent a divergent branch from the flageolet lineage leading to the recorder as we understand it today. Anthony Rowland-Jones (2014) has argued that rather than accepting these 14th-century relics to be recorders they should be viewed simply as improved flageolets with an extension by means of an additional finger hole to give a leading note in the lower octave, and a thumb hole to provide a stronger and more easily played middle tonic rather than using the awkward -23 456 fingering of the six-holed pipe. However, the home key of these instruments remained with six fingers down. Rowland-Jones further conjectures that it was not until the later decades of the 14th century that some makers hit upon the idea of raising the pitch of the fourth by about a quarter-tone. This enabled accidentals to be played with acceptable tone quality by putting two fingers down below an open hole in the lower octave, and by one finger in the upper octave. If the placing of the little-finger hole, and the bore profile, were then modified to give an interval of a whole tone, a tonic could then be played with seven fingers down. At the expense of the flageolet’s agility and two-octave compass, a chromatic duct flute came into being which could play along with a singer. The very portable recorder would have been an obvious aid to learning, rehearsing and even performing vocal music. Eventually, with three instruments, the piece could be repeated (‘recorded’ ) to give the singers a rest and a change of sound for the listeners.

In this context, I note that an interesting instrument which might be intermediate between the transitional recorders described above and the six-holed pipe was excavated in 1939 in Randers, Denmark (Kulturhistorisk Museum Randers, No. 5816). This is a bone duct flute made from the tibia of a sheep. It has a quadrangular window and a slightly curved labium, six finger holes, and a rear thumb hole above the frontal holes. Its date is uncertain, but has been placed between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries by the museum (Müller et al. 1972: 40). This points to an overlap of this kind of modified 6-holed pipe with the early recorder.

A late medieval recorder (DK-Copenhagen: Musikhist. Mus. Inv. D9745), together with other objects, was found in 1919 during an excavation in central Copenhagen by archaeologists from the Danish National Museum. The Copenhagen Recorder was not described until recently (Bergstrøm 2020). It cannot be dated precisely, but was found among “predominantly late medieval objects”, which suggests a date in the second half of the 15th century.

The Copenhagen recorder is well preserved, but extremely warped, and the block is missing. It is 28.3 cm long, made of boxwood, and has seven fingerholes on the front and a single thumbhole on the rear. The lowers fingerhole is doubled so that it can be played either right or left-handed. The outer profile is slightly waisted, narrowing from 20.5 mm at the top to c. 16.7 mm at fingerhole 4 from which it expands to 23.5 mm at the foot. The turning is far from smooth with a single ornamental groove at the end of the windway and the upper end of the window. Like the Tartu and Elbląg recorders, there is a flattened surface on the front of the instrument extending almost its full length. Rather than undercut, the somewhat oval fingerholes are slightly conical with the larger diameter at the outer surface. The windway is very short (22 mm) and there is no beak as such. Two holes on the side of the recorder in line with the middle of the block having a diameter of c. 4 mm suggest that the block was originally secured by a transverse peg or by means of a cord which might also have enabled the recorder to be suspended around the player’s neck. The window, labium and windway are crudely and irregularly fashioned. Part of the labium seems to have broken off. The internal bore consists of two cylindrical sections: the upper 12.7 mm in diameter, the lower c. 10.3 mm. Opening the lowermost finger hole produces a whole tone (Bergstrøm 2020).

In all essentials the Copenhagen recorder is indistinguishable from early renaissance forms of recorder, as we know them from surviving examples, iconography and texts of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

References cited on this page

- Bergstrøm, Ture. 2020. “A Late Medieval Recorder from Copenhagen.” Galpin Society Journal 73: 220, 240, 244.

- Blusiewicz, K. 2011. “Sprawozdanie z ratowniczych badań archeologicznych przeprowadzonych na działce miejskiej nr 123 w Pucku we wrześniu 2010 roku oraz lipcu i sierpniu 2011 roku [Report on the archaeological research carried out at the municipal plot No. 123 in Puck in September 2010 and July and August 2011].” Maszynopis w Archiwum Zakładu Archeologii Późnego Średniowiecza i Czasów Nowożytnych Instytutu Archeologii Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego [Typescript in the Archives of the Department of Archeology of the late Middle Ages and modern times, Institute of Archeology, University of Warsaw.]

- Bouterse, Jan. 1995. “Early Dutch Fipple Flutes, with Emphasis on the Seventeenth Century and Jacob van Eyck.” In The Recorder in the 17th Century: Proceedings of the International Recorder Symposium Utrecht, 27-30 August 1993, edited by David Lasocki, 77–90. Utrecht: STIMU.

- Carlick, Brian. 1975. “The Carlick Dordrecht Recorder.”

- Doht, Julia. 2006. “Die Göttinger Blockflöte [The Götingen Recorder].” Tibia 31 (2): 105–7.

- Fitzpatrick, Horace. 1975. “The Medieval Recorder.” Early Music 3 (4): 361–64.

- Gołembnik, Andrzej. 2000. “Płock we wczesnym średniowieczu [Płock in the Early Middle Ages].” In Historia Płocka w ziemi zapisana. Podsumowanie wyników dotychczasowych badań archeologicznych [History of Płock written in the ground. Summary results of previous archaeological research], edited by Andrzej Gołembnik, 13–48. Płock: Stowarzyszenie “Starówka Płocka.”

- Hakelberg, Dietrich. 2002. “Was von einer ‘Klangschaft’ blieb? [What Remains of a Soundscape?].” Archäologie in Deutschland – Das Magazin 4: 31–32. http://www.aid-magazin.de/Was-von-einer-Klangschaft-blieb.1723.0.html?&L=0&no_cache=1&sword_list[0]=hakelberg.

- Hakelberg, Dietrich. 1995. “Some Recent Archaeo-Organological Finds in Germany.” Galpin Society Journal 48: 3–12.

- Hakelberg, Dietrich, and Betty Arndt. 1994. “Eine mittelalterliche Blockflöte aus Göttingen. Mit einem einleitenden Beitrag von Betty Arndt.” Göttinger Jahrbuch, hrsg. vom Geschichtsverein für Göttingen und Umgebung e.V. 42 (S): 95–102.

- Hijmans, Ita. 2015. “Instrument onbekend. De reconstructievan een blokfluitconsort uit het midden van devijf- tiende eeuw [Unknown instrument. The reconstruction of a recorder consort from the middle of the fifth century].” Madoc 29 (4): 230–40. https://www.academia.edu/37971333/Instrument_onbekend_De_reconstructie_van_een_blokfluitconsort_uit_het_midden_van_de_vijftiende_eeuw_pdf

- Hijmans, Ita. 2016. Filling the gap, Eeen 15-eeuwse reconstructie in concert. https://fillingthegapreconstructionproject.wordpress.com/

- Hijmans, Ita. 2016. “Dordrecht-blokfluit.” Filling the gap: een 15e-eeuwse reconstructie in concert. 2016. https://fillingthegapreconstructionproject.wordpress.com/dordrecht-blokfluit/.

- Homo-Lechner, Catherine. 1996. Sons et instruments de musique au moyen age: archéologie musicale dans l’Europe du VIIe au XIVe siècles [Sounds and Musical Instruments of the Middle Ages: Musical Archaeology in Europe from the 7th to the 14th Century]. Collection des Hesperides. Paris: Editions Errance.

- Kalender, H.C. Willi A., Achim Langenbucher, Michael Meyer, Thomas Sauer, Andreas Spindler, and Wolfgang Spindler. 2009. “Vermessung mittelalterlicher Musikinstrumente. Hand-out zur Pressevorstellung. Donnerstag, 9. April 2009, 10.30. Bibliothek des Institut für Medizinische Physik, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg [Survey of Medieval Musical Instruments. Hand-out for Press Launch. Thursday, April 9, 2009, at 10.30. Library of the Institute of Medical Physics, University of Erlangen-Nuremberg].” Capella Antiqua Bambergensis. April 9, 2009. http://www.capella-antiqua.de/01-main-g/intro/media/Handout.pdf.

- Kirnbauer, Martin. 2002. “Musikzeugnisse des Mittelalter [Musical Finds from the Middle Ages].” Archäologie in Deutschland 6: 54–55.

- Kirnbauer, Martin, and Crawford Young. 2001. “Musikinstrumente aus einer mittelalterlichen Latrine.” Institutsbeilage der Schola Cantorum.

- Kunkel, Otto. 1953. “Ein mittelalterlicher Brunnenschacht zwischen Dom und Neumünster in Würzburg [A medieval well shaft between the Dom and Neumünster in Würzburg].” In Mainfränkisches Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Kunst, 5:293–309. Würzburg: Buchdruckerei Karl Hart.

- Lasocki, David R.G. 2023. “The Era of Medieval Recorders, 1300-1500.” In The Recorder, 1–47. Yale Musical Instrument Series. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300118704/the-recorder/.

- Moeck, Hermann A. 1967. “Typen europäischer Blockflöten in Vorzeit; Geschichte und Volksüberlieferung [Types of European Recorders in Antiquity; History and Folklore].” Moeck Verlag und Instrumentenwerk.

- Müller, Mette, Reidar Sevåg, Helga Jóhannsdóttir, and Bjórn Stürup. 1972. From Bone Pipe and Cattle Horn to Fiddle and Psaltery. Folk Music Instruments from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden. Edited by Mette Müller. Copenhagen: Musikhistorisk Museum.

- Naumann, Norbert. 1999. “Der Schatz aus der Latrine [Treasure from the latrine].” GEO Epoche 2: 116–23.

- Poplawska, Dorota. 2014. “Drewniane flety proste z wykopalisk archeologicznych na terenie Europy [Wooden recorders from archaeological sites in Europe].” Sylwan 158 (1): 72–80.

- Popławska, Dorota, and Hubert Lachowicz. 2014. “Drwniane flety proste z wykopalisk archeologicz na tereni Europe [Wooden recorders from archaeological sites in Europe].” Sylwan 158 (1): 72–80.

- Reiners, Hans. 1997. “Reflections on a Reconstruction of the 14th-Century Göttingen Recorder.” Galpin Society Journal 50: 31–42.

- Rowland-Jones, Anthony. 2006. “The First Recorder …? Some New Contenders.” American Recorder 48 (2): 14–20.

- Rowland-Jones, Anthony. 2014. “When Is a Recorder Not a Recorder?” FoMRHI Quarterly 127: 6–10. http://www.fomrhi.org/vanilla/fomrhi/uploads/bulletins/Fomrhi-127/Comm%202008.pdf.

- Rowland-Jones, Anthony. 1996. “La flauta de pico en el arte catalán [The Recorder in Catalan Art]. 1a Parte. Alrededor de 1400: la invención de la flauta de pico [Around 1400: The ‘Invention of the Recorder’]. 2a Parte. El siglo XV [The Fifteenth Century].” Revista de flauta de pico, 6: 15–20; 7: 9–15.

- Thijsse, Wilhelmus Hermanus. 1949. Zeven eeuwen Nederlandse muziek. [Seven Centuries of Dutch Music]. Rijswijk: V.A. Kramers.

- Tonderę, Marian. 1966. “Średniowieczne zabytki archeologiczne odkryte w Nysie [Medieval archaeological artifacts discovered in Nysa].” Opolski Rocznik Muzealny 2: 151−158.

- Tvauri, Andres, and Rivo Bernotas. 2005. “Archaeological Investigations Carried out by the University of Tartu in 2005.” AVE, 101–10.

- Tvauri, Andres, and Taavi-Mats Utt. 2007. “Medieval Recorder from Tartu, Estonia.” Estonian Journal of Archaeology / Eesti Arheoloogia Ajakiri 11 (1-2): 141–54. http://www.kirj.ee/public/Archaeology/2007/issue_2/arch-2007-2-3.pdf.

- Utt, Taavi-Mats. 2006. “The Tartu Recorder.” ERTA Newsletter 23: 2.

- Weber, Rainer. 1976. “Recorder Finds from the Middle Ages, and Results of Their Reconstruction.” Galpin Society Journal 29: 35–41.

Cite this article as: Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2026. Recorder Home Page: A memento: the medieval recorder: Surviving specimens. Last accessed 21 February 2026. https://recorderhomepage.net/instruments/a-memento-the-medieval-recorder/surviving-specimens/