Leonardo’s inventiveness manifested in his many designs of all kinds of machines and artifacts, some of them were precursors of objects being built centuries later, like the submarine or the helicopter. Some of his designs were musical instruments, for example, two flutes drawn on sheet 110r of the Atlantic Codex.

— Emmanuel Winternitz (1982).

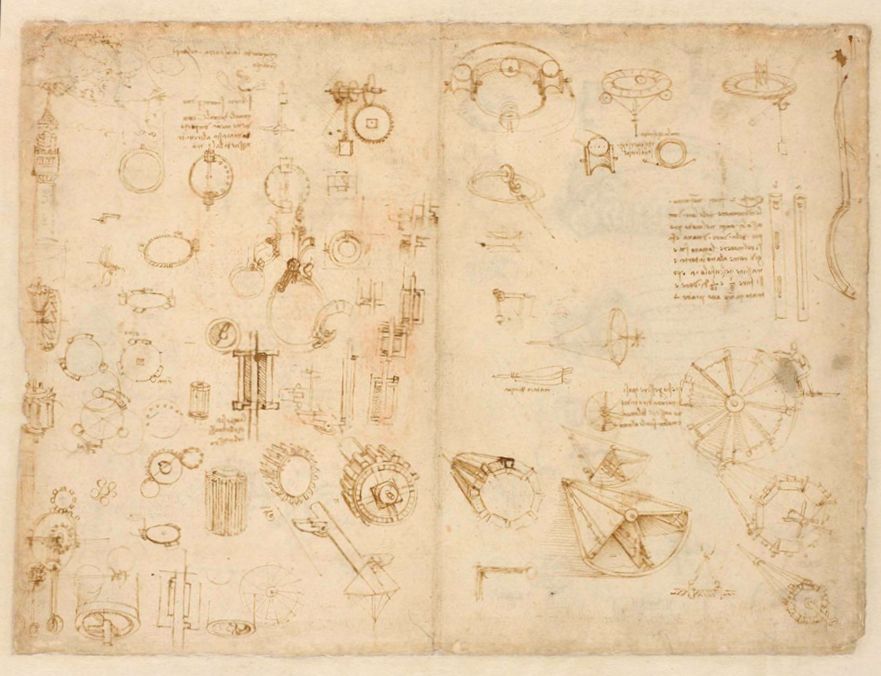

The page of Leonardo da Vinci’s notes in Codex Atlanticus Folio 1106r (1498) is full of drawings and appears as chaotic as most of his writings.

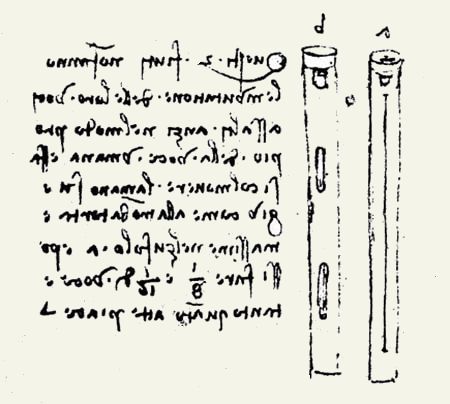

Among the various subjects is a paragraph tied to a sketch of two unusual end-blown duct flutes which allow players to vary the pitch from one note to another in a continuous way, without fixed intervals, because of the smooth, uninterrupted fissure(s) they have instead of the more usual finger holes. Following Leonardo’s indications, a flautist can modulate a note’s intonation to their liking by moving their hands over the fissure, thus producing all the intermediate sounds among the hypothetical positions of the holes on a traditional flute (as Leonardo writes, also at 1/8 and 1/16 tonal intervals).

Accompanying the drawings, a brief description (written in reverse) reads:

Questi due fiuti non fanno le mutazione delle loro voci a salti, anzi nel modo proprio della voce umana; e fassi col moverela mano su a giu come alla tromba torta, e massime nel zufolo a; e possi fare 1/8 e 1/16 di voce, e tanto quanto a te piace.

[These two flutes do not produce sounds at intervals but rather in the manner of the human voice. This sound is produced by moving your hand up and down, as on a folded trumpet and more so on pipe a; and you can also produce sounds at tone intervals of 1/8 and 1/16, just as you want.]

Note that Leonardo was left-handed and used a form of mirror writing. Obtaining an eighth or sixteenth of the tone obviously means to reach the upper octaves; moving the hand up and down evidently means not to stop prearranged finger holes but to move along the slits to change pitch gradually. These have been called fissure flutes or glissando flutes since one note slides into another of lower or higher pitch passing by all intermediate frequencies.

Unfortunately, the text does not include data on the dimensions of the flutes or clear clues to their intended use. In experiments carried out in 2019 by Italian recorder maker Giacomo Andreola it was found that flute b (with two slits) can work if it is a little longer than flute a, because its two grooves are shorter but, in that case, they cannot be closed with one hand and in da Vinci’s drawing you can see that it has a length equal to flute a (with a single slit). This raises the question of whether da Vinci was able to build and operate his flutes and observe the functional effects described in the text. In the case of flute a, the groove must be less than the length of the player’s extended index finger; in flute b each of the two grooves must be equal to or shorter than the width of four fingers together. In Giacomo’s experimental reconstructions flute b was found to be the most effective and efficient, with each slot 5.5 cm long.

Giacomo’s reconstructed fissure flute can be seen and heard in two performances as follows:

La Bassa Castiglia by G. Ebreo da Pesaro (c.1420 – p.1484)

Anne Kirchmeier Casularo (fissure flute), Katia Chevrier, (recorder)

Madrigal Forsi che sì, forsi che no, by Marchetto Cara (c.1465-1525)

Anne Kirchmeier Casularo (fissure flute), Sławomir Zubrzycki (viola organistra)

The viola organistra, another of Leonardo’s astonishing musical inventions, was built by Sławomir Zubrzycki himself in 2012.

Over the last 120 years, various attempts have been made to create continuously variable pitch wind instruments. A notable approach in the present context was the H.N White Company’s King C Saxoprano produced in the 1920s. The front surface of the conical body of the instrument has a fissure above which is suspended a leather strap held in place by an adjustable fastener. Different pitches are produced by pushing down on the strap at different points on the tube to lower the sounding length of the instrument and opening an octave key to extend the range. A bell was added to give the instrument a more saxophonic appearance. A number of variants on this design soon appeared, such as the English Swanee Sax (1927), and the French Mellosax (1929). In the 1990s, the American Bart Hopkin extended this idea to create his experimental ‘Moe family of instruments, including ‘Moe’ clarinet, saxophone, membrane pipe, and flute (actually a recorder).

More recently, Hungarians Dániel Váczi and Tóbiás Terebessy combined forces in 2016 to explore new possibilities for woodwind musical instruments. Their first prototype was quite basic: a bamboo tube with a slot and a fridge magnet attached to it, combined with the mouthpiece of a saxophone. This experiment confirmed that the concept worked, and from there the Glissotar was born, in essence a slide tárogató (a wooden saxaphone-like instrument used in Hungarian traditional music). Over the following years, Dániel and Tóbiás worked closely with a team of instrument makers to refine the instrument’s design, materials, and components.

In its final form, the Glissotar stands out with its unique design and precision fabrication. It features a longitudinal slot along the instrument’s conical tube, covered by a magnetic strip that allows for smooth pitch changes. Instead of traditional tone holes, the player can press the magnetic strip at any point in combination with two octave keys to produce any pitch within a continuous range of 2½ octaves.

Váczi & Terebessy (2024) write that their glissonic system can be used on various wind instruments: flute, recorder, clarinet, saxophone, tarogato, oboe, etc. Currently in development are a Glissoboe and a Glissoflute.

Meanwhile, they will shortly release their Glissopipe, a series of inexpensive 3D printed plastic instruments available in three tunings: sopranino (f”), soprano (c”) and alto (g’) tunings, each available in three colours (orange, white and blue).

There’s plenty of information about these instruments on their website via the above link, where you can find an interview with Dániel Váczi, an article by composer and author Chris Weisman explaining what makes the Glissopipe unique and why it immediately invites exploration, listening, and playful musical discovery. There are also images, sound clips and some technical details. And you will also find information on how you can get involved, since this is a Kickstarter project.

An enthusiastic and informative review and demo of the Glissopipe by Sarah Jeffery can be found on her Team Recorder YouTube site.

The Glissopipe, opens up a new world of microtonality hitherto difficult to access using the conventional recorder. And it represents the apotheosis of Leonardo da Vinci’s fissure flute first proposed in 1498.

As a bonus, 3D printing enthusiasts can download free model files from Glissonic Instruments for the Glissonardo, based on Leonardo’s original fissure flute (type a).

References

- Andreola, Giacomo. 2020. Costruzione Flauto Leonardo da Vinci. YouTube: https://youtu.be/rQUEq0iwaBQ

- Andreola, Giacomo. 2021. da Vinci ARCLV Fissure Flute.

- Cohen, Paul. 1994. Vintage saxophones revisited. Voices of the slide saxophone. Part II. Saxophone Journal September/October: 6-8. https://glissonic.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/FULL_Paul_Cohen_Vintage_Saxophones_Revisited.pdf

- Da Vinci, Leonardo (1478-1519). Codex Atlanticus. In Italian and English as The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, Mrs R.C. Bell, ed. Jean Paul Richter. 1888. Project Gutenberg. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5000

- Hopkin, Bart. 2021. The ‘Moe family of wind instruments. Tempe Arizona. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bsiKxaxiqcw

- Hopkin, Bart. 2024a. Musician and Instrument Designer. Tempe Arizona. https://barthopkin.com/

- Hopkin, Bart. 2024b. ‘Moe Flute. Tempe Arizona. https://barthopkin.com/instrumentarium/moe-flute/

- Jeffery, Sarah. 2026. Trying the New Glissopipes, Review and Demo. Team Recorder. Amsterdam. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WkO2SY7WfpI.

- Lander, Nicholas S. 1996–2026. Recorder Home Page: Leonardo da Vinci’s Recorders (2026). https://recorderhomepage.net/leonardo-da-vincis-recorders/

- Museum Leonardo. 2019. Il Mondo di Leonardo: The Great Continuous Organ brings Leonardo’s musical gifts back to life. Press release. Leonardo3 Research Centre, Milan. http://www.leonardo3.it/data/press_42993/fiche/321/20190624-leonardo3-pr-greatcontinuousorgan_9df1c.pdf

- Museum Leonardo. Undated, accessed July 2021. Machines: Glissando Flutes. Leonardo3 Research Centre, Milan. http:\www.leonardo3.net\en\l3-works\machines\1479-glissando-flutes.html

- Posada, Daniel F. Undated, accessed July 2021. Da Vinci Music Machines. Includes a suggestion for making Leonardo’s ‘flute a‘ (with a single slit) more practical somewhat in the manner of a Swanee whistle (see image above). https://danfp.artstation.com/projects/A9DKno

- Váczi, Dániel & Tóbiás Terebessy 2024. Glissonic Instruments. Budapest. https://glissonic.com

- ———. 2025. Glissopipe. Budapest. https://glissopipe.com/

- ———. 2026. Glissanardo. Budapest. https://www.printables.com/model/1516682-glissonardo

- Winternitz, Emmanuel. 1982. Leonardo da Vinci as a Musician. Yale University Press. https://www.academia.edu/27695054/Leonardo_da_Vinci_as_a_musician

- Zammattio, Carlo, Augusto Marinoni & Anna Maria Brizio. 1981. Leonardo der Forscher. Belser Verlag, Zürich, S. 125. Abb. 6. In English as Leonardo the Scientist, transl. Alan Brinkley, McGraw-Hill (1981).

Cite this article as: Nicholas S. Lander. 1996–2026. Recorder Home Page: Leonardo da Vinci’s Recorders. Last accessed 10 March 2026. https://recorderhomepage.net/leonardo-da-vincis-recorders/